As World Aids Day approaches, Jonathan deBurca Butler discovers that although people with HIV can now expect to live full lives, stigma still exists.

Tonie Walsh was diagnosed HIV- positive on a Friday afternoon. As he walked out of St James’s Hospital and into the start of the Dublin weekend, he felt a strange compulsion to tell everyone around him.

“I came out of The GUIDE Clinic for STIs in James’s and had this ridiculous urge to scream my new-found status at the top of my voice to the people standing at the Luas stop,” he recalls. “But I demurred and I went up to work. I remember I was late, and I met Rory O’Neill (Panti) who I was running a club with at the time. Rory asked me where I was. I told him where I had been and told him that I had got my result. ‘And?’ he asked me. And I said: ‘Well, I’m positive’. And without missing a heartbeat he turned to me and said: ‘about bloody time'”.

Looking back on that day 12 years ago, the 57-year-old Dubliner says “getting the news in middle-age felt like an anti-climax”.

As a gay man living through the mid 1980s and 1990s, Tonie had lived through what he calls ‘The War’ – a period when he lost “an increasing amount of friends and lovers” and spent much of his time “wondering when I was going to be next”.

“I think anyone who lived through those horrors and that period will remember the levels of hysteria that existed around the time and we remember the difficulty of trying to advocate around intimacy at a time when contraceptives were illegal,” he says. “We had a Government that was browbeaten by what we now rightly regard as a rather moribund and dodgy Catholic morality around sex and sexual behaviour and it just wasn’t a good time to live through.”

The fear and ignorance around the condition was palpable and it did not help that there were conflicting reports coming from the medical world about how it could be transmitted. Public service adverts featured dark images of faceless reapers claiming vast swathes of corpses and yet the information was vague. One moment it could be caught from kissing, the next it could be caught from using the same cup. In playgrounds up and down the country the cries “you have Aids” were heard coming from the mouths of primary school children who couldn’t possibly have known what exactly they were talking about. But nobody did. Not even their parents who would brandish people they did not like the look of ‘having the look of someone with Aids’.

Early on it was branded the Gay Plague and for the many who perceived gay life as an endless stream of debauchery, it was seen as being good enough for them. It probably helped so-called normal people to feel safe that it was only people who led so-called alternative lifestyles who could, they thought, get the disease. And while there might have been, on the surface at least, more sympathy offered to people who contracted the disease through contaminated blood there was little dignity for them.

In 2000 an investigation into infected blood transfusion products, the Lindsay Tribunal, heard how a father discovered his 10-year-old son was HIV positive when he bumped into a consultant on the street. Having had his son tested in 1984 and having heard nothing, he assumed the boy was clear but when the consultant asked how the counselling was going, the penny dropped; the doctors knew but the family didn’t and they were never offered counselling. He told the tribunal that over the last days the boy had to be fed with a tube.

“He was so thin you would be afraid to look at him,” he told the tribunal. “His eyes were like golf balls.”

Another witness told how her family decided to bring her dead brother back home in the car rather than leave him in hospital where the policy was to place the corpses of people with Aids in a body bag. It was a hell that for the most part went unnoticed and ignored.

And it was not just Ireland. In the UK, certain newspapers demonised homosexuals and drug users. The U.S.A. fared little better. When actress Elizabeth Taylor looked around her and saw people in her industry dying by the score she decided she wanted to raise awareness and funds.

In 1991 she founded the Elizabeth Taylor Aids Foundation. Initially, Hollywood showed it’s true superficial colours and responded with apathy. Tinsel Town did not mind death but this kind of death was insufficiently glamorous.

“No one really wanted to get into it with me,” she said. “I had to take the position, ‘I will not be ignored, so get used to hearing about this from me because you will be, for a long time, or for however long it takes’. I started noticing that my calls weren’t being returned. I must say, that was a first in my life.”

To her eternal credit, Taylor never gave up and eventually people rowed in behind her.

“People thought you could become HIV-positive by breathing the same air,” says Tonie. “There was hysteria around it and a lack of knowledge. When my friends started dying we adjusted to the devastation and the horror in our midst,” he recalls. “Trying to grapple with that destruction and the never-ending funerals, the fundraising for basic facilities to allow people die with dignity and the absence of State funding, it never seemed to end, so you always thought you’d be next.

Then 1996 arrives and there are new antiretroviral therapies and now people are living and surviving and then we realise that HIV is a manageable condition not unlike diabetes. And so I had survived all this and I had to sort of modulate that survivor guilt. Our worlds had been upended. It was chaotic, destructive, tawdry, people died shabby, lonesome deaths and for those of us that survived, we were relieved but also guilty. So when I got my news years after all this…and now I just pop a pill and we live in a very different climate, hence the anti-climax.”

In 1996 the discovery of protease inhibitors which specifically targeted and stopped the spread of the virus in the body meant that treatment for the HIV virus took a giant leap forward. Almost overnight (in some countries at least) something that was considered a death sentence was turned into a condition that could suddenly be managed. The effect was immediate and quite amazing with deaths in the United States, for example, falling from a peak of 50,000 in 1995 to 18,000 two years later. While it couldn’t be cured, it could at least be tamed.

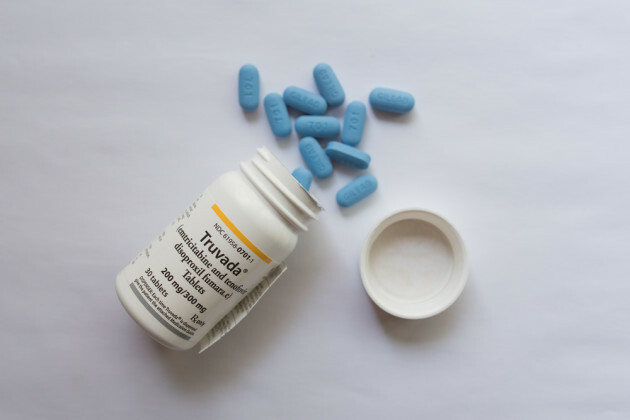

“People with HIV now are living with a chronic illness so it’s not what it was twenty years ago where you ended up with a deficient immune system and would succumb to illness as a result of that deficiency,” says Dr Shay Keating, associate specialist in sexual health and HIV at St James’s Hospital. “Now what we can do is put people on medication and in a matter of months make sure that the virus is not detectable in their blood and that their immune system recovers and is back to being as good as possible. Over the last eight to 10 years the drugs have improved again and so now we have many people on what’s called a single tablet regimen.”

And it is a regimen that, in order to be effective, has to be rigidly adhered to.

Tonie Walsh takes a pill in the morning with around 500 calories of food for better absorption. Although he is overwhelmingly positive about the treatment and is “grateful he lives in a country like Ireland” where the Government subsidises the €40 pill, he is aware that like any long-term treatment there are potential side effects. With the particular drug he takes, for instance, there is an increased risk of cholesterol and heart disease but the alternative is not a choice worth contemplating.

“HIV is nasty,” he says. “It finds its way into your system and hides in there. It lodges there and it cloaks itself and what the antiretrovirals do, is disable it but it’s still there, it doesn’t get rid of it and all it’s waiting for is the opportunity for your body to make a space for it to multiply and take over the host. So it’s really important that people on the treatment adhere to the regimen that they have because if you don’t, HIV will come back and bite you on the ass.”

Indeed, there have been cases in Ireland in the last five years where people have died because of full- blown Aids. Either because they chose not to take the medication or they were not aware of the condition they had.

According to HIV Ireland, there are currently around 4,000 people in Ireland who are knowingly living with HIV. There could well be more and the reason we do not know as much as we should is down in many respects to a lack of education around sex and sexual health.

A cohesive policy around sex education was only enacted by Government for the first time two years ago and while there has been progress around the provision of testing it is slow moving and urban-centric.

Another consequence of this lack of education (or at least the reluctance to talk about sexual health) is that while those with HIV now lead undoubtedly healthier and hopeful lives, there is still a stigma attached to having the illness.

A recently published Knowledge and Attitudes Survey from HIV Ireland revealed that 10pc of people still believed that HIV could be transmitted by sharing a glass, 70pc per cent believed it could be transmitted through biting, while nine pc believed that transmission occurs through toilet seats. Remarkably, when it comes to knowledge of transmission those in the 18-24 bracket were less in tune than their older counterparts – 19pc of 18-24-year-olds believed HIV could be passed through coughing for example, while just 13pc over that age considered it a possibility.

Most startling of all was the fact that just 19pc of those surveyed were aware that the risk of someone who is taking effective treatment passing on HIV through sex is extremely low.

“Things have changed significantly around HIV since the mid-1990s with improvement around treatment,” says Niall Mulligan, director of HIV Ireland. “You would think that would lead to a corresponding decrease in stigma but anecdotally we’ve known for quite a while that’s not always the case. There were some very positive things that came from the survey in terms of acceptance of people living with HIV and a better knowledge of key transmission routes but people still had some real myths around transmission routes like bathrooms and coughing and so on.”

As well as examining attitudes towards HIV among the general populace, the survey asked people with HIV about their own attitudes.

“Most worrying was how being HIV made people feel about themselves,” says Mulligan – “17pc of those surveyed with HIV said they had contemplated suicide over the last year, much higher than the average in the general population. And I think we can link that back to stigma, a fear around disclosing status and the impact that has on their relationships either with family or if they are getting into new relationships, they have to think about this all the time.

“There is a great fear of rejection among people with HIV. Something like 60pc of people felt they would be rejected in a relationship and for 38pc that was in fact a reality.

“When it first came on the scene, HIV and Aids had different target groups,” says Tonie Walsh. “It targeted haemophiliacs, drug users, sex workers, gay men and when you look at those demographics, apart from the haemophiliacs who were seen as kind of innocent if you like, they all brought with them a veneer of ‘transgressiveness’ or criminality and that attached itself to public discourse around HIV and Aids.”

“I’m quite flippant about my status,” Tonie continues, “and I have been from day one but I don’t think there are many who are and I still think that says a lot about the stigma around it. People are worried they’re going to feel judged. My attitude is, I don’t care who knows. There are bigger things to worry about. I mean being 57, I worry about wrinkles or my sagging bottom. There are much more important things to worry about.”

Robbie Lawler is unlikely to witness the generational destruction experienced by Tonie.

“I was born in 1991 and was educated in a Christian Brothers school so I bypassed all and any HIV messaging or education,” he says. “I knew nothing about it. I knew no one who passed away because of Aids. My diagnosis must have been a completely different experience to that of Tonie’s.

“But everyone who is diagnosed with HIV automatically becomes part of this Aids legacy; what happened in the past, what could have been, what is currently happening, the future of HIV, society’s perception of us and the virus as a whole. While our experiences have been different, there are many shared commonalities.”

Like the majority of people with HIV in Ireland, Robbie contracted the virus through unprotected sex.

“I was 21 when I went for my very first sexual health check,” he recalls. “I was called back into St James’s GUIDE clinic three weeks later because my gonorrhoea test came back inconclusive. I hadn’t a clue what was in store for me. When the doctor told me my HIV test came back positive I had no idea how I was getting this diagnosis. I was supposed to head to Australia to work a few months later but I was told that people living with HIV couldn’t get residency visas back then. So my diagnosis was a bit of a double whammy. I was devastated. I knew nothing about HIV. I didn’t know the difference between HIV and Aids. I was telling all my friends I had Aids for a while. It shows my ignorance. I am quite well-educated and would have been on the scene during college years yet I knew no one living with HIV, let alone know it was in the country. I honestly felt like I was the only young person in Ireland living with HIV and that can be quite a lonely feeling.”

Robbie is currently on his fifth round of treatment. He explains that he has had a few bad experiences on different medications and equates the search for the right drug as “like women looking for the right contraception pill, you have to find the right one that suits you best”.

“The medication that has recently come out is so easy to take,” he says. “Thanks to my medication I can live as long as anyone else and I know I cannot pass on HIV. My boyfriend is negative and he just cannot get HIV off me. Simple as that.”

Like Tonie, Robbie feels “blessed to live with HIV in this time” but he is only too keenly aware that there is still a shadow around the condition.

There are, for him, different stigmas in different situations for those with HIV. Active discrimination is one obvious offence but it is one that Robbie feels more able to forgive.

“Why are you with Robbie, he’s a risk?’ I’ve heard those kinds of things but how can I be angry? I used to be someone who didn’t know the difference between HIV and Aids,” he says. “These are people who are saying things out of ignorance. I’m an educator and people change their whole perception of HIV once they learn about it and get to put a face to such a silenced virus.”

Campaigners, crusaders and those who left too soon

Thom McGinty aka The Dice Man

Anyone who rambled up and down Grafton Street in the 1980s and early 1990s will remember the elegant Scot who wowed children big and small with his exaggerated winks and nods. When he went on to The Late Late Show in 1994 and announced he had Aids it was a watershed moment. Here for the first time was someone we felt we knew, someone who lived among us with Aids and we adored him. He passed away in February 1995.

Freddie Mercury

For a long time Freddie Mercury kept his health status to himself. As his partner, Carlow-born Jim Hutton described, “he felt it was his business”. Shortly before his death he released a statement in which he said he had Aids. Jim described their last conversation years later. “[It] took place a few days before he died. It was 6am. He wanted to look at his paintings. ‘How am I going to get downstairs?’ he asked. ‘I’ll carry you’, I said. But he made his own way, holding on to the banister. I kept in front to make sure he didn’t fall. I brought a chair to the door, sat him in it, and flicked on the spotlights, which lit each picture. He said, ‘Oh they’re wonderful’. I carried him upstairs to bed. He said, ‘I never realised you were as strong as you are’.”

Magic Johnson

NBA superstar Magic Johnson announced that he was infected with HIV in 1991. Initially he announced his retirement from the game but returned and played for numerous seasons on and off thereafter. Arguably, his announcement did more than anyone at the time to break stigma around HIV and Aids.

Vincent Hanley

From 1984-87, young people across Ireland would rush back from Sunday Mass to listen to the dulcet tones of the only preacher they really wanted to hear, the easy-going Fab Vinny. To the few that didn’t have family there, he was our only connection to New York and the music of the United States. Hanley, a hero to a generation, was the first Irish celebrity to die of an Aids-related illness, though it was not something that was confirmed publicly until years later.

Gia Marie Carangi

An American model and was considered by many the first supermodel. By the early 1980s she had become addicted to heroin and her modelling career went rapidly downhill. In 1986, she died of Aids-related complications, becoming one of the first famous women to die of the disease.

This article first appeared in the Sunday Independent on 26th of November 2017.